Shameless plug: I published this post in the r/learnmachinelearning subreddit where it became a top post of the week in October 2020!

Please tell me more

Sometimes the details behind mathematical proofs are relatively easy to infer, but when they’re not don’t we wish the details were spelt out? Sometimes books or online sources show steps 1, 2, and 5 without steps 3 and 4. And steps 1, 2, and 5 are sometimes better dealt with if the logic were fully fleshed out. At other times, all the steps are shown but in a terse or hasty way. Such is the case, in my opinion, when it comes to understanding maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) for logistic regression gradient descent. After working through the gory details by hand and different color inks, I felt the need to illustrate it to benefit anyone who may wish to see a full breakdown of how the gradient update function for logistic regression is derived. This blog post is inspired by these lecture notes from Stanford.

To be clear it’s definitely not necessary to understand the mechanics behind the derivation in order to be a good ML practitioner, but since MLE with logistic regression tends to be the springboard by which neural networks are introduced, understanding it can lead to greater appreciation and comprehension of deep learning.

Get some caffeine - this will be long, but rewarding!

Part 1: Motivating Logistic Regression

We want to extend the linear regression model to handle classification. We all know the standard linear regression equation with \(p\) predictors:

\[\large y = \theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p\]

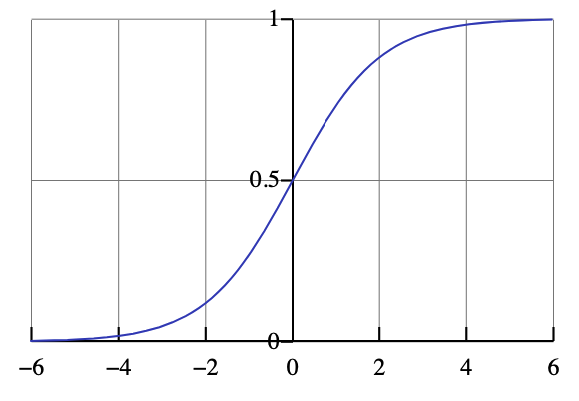

We want to modify this so that outputs fall between \(0\) and \(1\) for classification purposes. This is classically done using the logistic function:

\[\large \sigma (z) = \frac{e^{z}}{1+e^z}\]

where \(z\) is some arbitrary scalar input.

The logistic function. Source: Wikipedia

Our new equation is now:

\[\large p(y) = \frac{e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}} = \sigma(y)\]

However, we’d like to work with a linear function, so instead of working with \(p(y)\), we use the odds of \(y\) by dividing \(p(y)\) by \(1-p(y)\). This is equivalent to saying divide \(\sigma(y)\) by \(1-\sigma(y)\)

\[\large 1 - p(y) = 1 - \frac{e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}} =\frac{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}} - \frac{e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}\]

\[\large 1-p(y) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}\]

Carry out the division of \(p(y)\) and \(1-p(y)\) by multiplying the former by the reciprocal of the latter:

\[\large \frac{p(y)}{1-p(y)} = \frac{e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}} * \frac{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1} = e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}\]

By taking the natural log of both sides, we get

\[\large ln\left (\frac{p(y)}{1-p(y)} \right ) = \theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p\]

This says that the log-odds that \(y=1\) is given by \(\theta_{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p\)

Part 2: Introducing MLE

We just derived the functional form of logistic regression, but when it comes to determining optimal values of \(\theta_{0}, \theta_{1},..., \theta_{p}\), we usually use the formula for \(p(y)\). As a reminder

\(\large p(y = 1) = \frac{e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}\)

To avoid the redundancy of the RHS, we’ll substitute it with \(\pi\), so that

\(\large \pi = \frac{e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}{1 + e^{\theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p}}\)

This implies \(p(y = 0) = 1 - p(y = 1) = 1 - \pi\)

A way to reformulate this is by noting that

\(\large p(Y = y) = \pi^y(1-\pi)^{1-y}\), with \(Y\) being a random variable describing the values any particular instance can take on, which for binary classification is \(0\) or \(1\). So:

if \(y=1\), \(p(Y = 1) = \pi^1(1-\pi)^{1-1} = \pi\)

if \(y=0\), \(p(Y = 0) = \pi^0(1-\pi)^{1-0} = 1-\pi\)

as just stated above. We use this reformulation since it provides a single equation to calculate the probability of Y taking on \(0\) or \(1\).

If we assume the probability that each instance in our data belongs to either \(Y = 0\) or \(Y=1\) is independent, then the total probability of observing all our instances belonging to the classes we observe in our data (given our choice of thetas) is the likelihood, a simple application of the multiplication rule in probability for independent events:

\(\large L = P(Y_1 = y_1, Y_2 = y_2, ..., Y_m = y_m) = \prod_{i=1}^{m}\pi^{y^{(i)}}(1-\pi)^{1-y^{(i)}}\)

There are \(m\) instances in our dataset. We’re trying to determine the thetas that will maximize this likelihood function.

Part 3: Prepping for gradient ascent

To make things easier, we’ll do two things:

convert the likelihood to the log likelihood, so that we can deal with sums instead of products

perform gradient ascent for just a single instance to motivate how to update the logistic regression loss function for all instances.

Examining gradient ascent for a single instance will make notation easier. For a single instance the likelihood \(L\) is:

\(\large L = \pi^y(1-\pi)^{1-y}\)

Taking the natural log on both sides to get the log-likelihood \(LL\):

\(\large LL = ln\left [\pi^y \cdot (1-\pi)^{1-y} \right ]\)

\(\large LL = ln(\pi^y) + ln\left [ (1-\pi)^{1-y} \right ]\)

Using properties of logs, we can bring the exponents to the front:

\(\large LL = y\,ln(\pi) + (1-y)\,ln(1-\pi)\)

This is our cost function.

Part 4: Gradient ascent using the Chain Rule

Photo by Willian Justen de Vasconcellos on Unsplash

Now we’re ready to perform the biggest part of the whole derivation. We will take the partial derivative of the log-likelihood \(LL\) with respect to each theta for our single instance, all using the Chain Rule from calculus.

To avoid overloading the letter y, we’ll use \(g\) to denote the linear combination of inputs, so that

\(\large g = \theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p\)

and hence

\(\large \pi = \sigma(g)\)

Now observe that \(LL\) is a function of \(\pi\), and \(\pi\) is a function of \(g\), and \(g\) is a function of the \(\theta_j\)’s, where \(j = 1, ..., p\).

Applying the Chain Rule, this implies

\(\boxed {\large \frac{\partial LL}{\partial \theta_j} = \frac{\partial LL}{\partial \pi}\,\frac{\partial \pi}{\partial g}\,\frac{\partial g}{\partial \theta_j}}\)

4.1: Partial of \(LL\) with respect to \(\pi\)

Let’s start with \(\frac{\partial LL}{\partial \pi}\). Since

\(\large LL = y\,ln(\pi) + (1-y)\,ln(1-\pi)\)

then by applying the Product Rule:

\(\large \frac{\partial LL}{\partial \pi}\ = y\,\cdot \frac{\partial}{\partial \pi}\,ln(\pi)\, + ln(\pi)\,\cdot \frac{\partial}{\partial \pi}\,y\ + (1-y)\,\cdot \frac{\partial}{\partial \pi}\,ln(1-\pi) + ln(1-\pi)\,\cdot \frac{\partial}{\partial \pi}\,(1-y)\)

The second and fourth summands equal \(0\) since neither \(y\) nor \(1-y\) include \(\pi\). So this simplifies to

\(\large \frac{\partial LL}{\partial \pi}\ = y\,\cdot \frac{1}{\pi} - (1-y)\cdot \left ( \frac{1}{1-\pi} \right ) = \boxed{\frac{y}{\pi} - \left ( \frac{1-y}{1-\pi} \right )}\)

4.2: Partial of \(\pi\) with respect to \(g\)

Now we move to the second portion of the partial of the log likelihood.

\(\large \frac{\partial \pi}{\partial g} = \frac{\partial}{\partial g}\,\left ( \frac{e^g}{1+e^g} \right )\)

This is since \(\pi = \sigma(g)\), and plugging \(g\) into the logistic function, \(\sigma(g) = \frac{e^g}{1+e^g}\)

Using the Quotient Rule

\(\large \frac{\partial \pi}{\partial g} = \frac{(1+e^g)\,\cdot\frac{\partial}{\partial g}(e^g)\, - (e^g)\left ( \frac{\partial}{\partial g}\,(1+e^g) \right )}{(1+e^g)^2} =\frac{(1+e^g)(e^g)\, - (e^g)(e^g)}{(1+e^g)^2} = \frac{e^g + (e^g)^2 - (e^g)^2}{(1+e^g)^2} = \boxed{\frac{e^g}{(1+e^g)^2}}\)

4.3: Partial of \(g\) with respect to \(\theta_j\)

Lastly we deal with perhaps the easiest part of the derivation.

\(\large \frac{\partial\,g}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \frac{\partial }{\partial \theta_j}(\theta_0 + \theta_1x_1 + \cdots+\theta_px_p) = \boxed{x_j}\)

Any terms that don’t contain \(\theta_j\) are considered constants, and taking the partial of those terms equals \(0\), leaving us with just \(x_j\)

Part 5: Putting it all together

Whew! Let’s put all the components from 4.1 to 4.3 together.

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \left ( \frac{y}{\pi}-\frac{1-y}{1-\pi} \right )\left ( \frac{e^g}{(1+e^g)^2} \right )x_j\)

We can simplify the middle term by noting that

\(\frac{e^g}{(1+e^g)^2} = \frac{e^g}{1+e^g}\left ( \frac{1}{1+e^g} \right ) = \frac{e^g}{1+e^g}\left ( 1-\frac{e^g}{1+e^g} \right ) = \sigma(g)[1-\sigma(g)] = \pi(1-\pi)\)

So then:

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \left ( \frac{y}{\pi}-\frac{1-y}{1-\pi} \right )\left ( \pi(1-\pi) \right )x_j\)

Bringing terms under a common denominator for the first term on the RHS:

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \left ( \frac{y(1-\pi)}{(1-\pi)\pi} - \frac{(1-y)\pi}{(1-\pi)\pi} \right )\left ( \pi(1-\pi) \right )x_j\)

Simplifying:

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \left ( \frac{y(1-\pi) - \pi(1-y)}{(1-\pi)\pi} \right )(\pi(1-\pi))x_j\)

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = (y-y\pi-\pi+y\pi)x_j = (y-\pi)x_j = [y-\sigma(g)]x_j\)

Part 6: Polishing up

We’ve fleshed out the tough stuff. But remember our derivation was just for a single instance. As there are \(m\) instances, we need to update \(\theta_j\) by taking all those instances into account.

So instead of just

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = [y-\sigma(g)]x_j\), we make this:

\(\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \sum_{i=1}^{m}[y^{(i)}-\sigma(g)]x_{j}^{(i)}\)

It’s additive because, as explained in Part 4, the log likelihood (\(LL\)) allows us to use sums instead of products.

What was \(g\) again? \(g = \theta _{0} + \theta _{1}x_1 + \cdots + \theta _{p}x_p\). In matrix notation this would be expressed as \(\boldsymbol{\theta}^T\mathbf{x}\). So then:

\(\boxed{\large \frac{\partial\,LL}{\partial\,\theta_j} = \sum_{i=1}^{m}[y^{(i)}-\sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}^T\mathbf{x}^{(i)})] x_{j}^{(i)}}\)

Now we know our update rule for any particular \(\theta_j\) and learning rate \(\eta\):

\(\large {\theta_{j}^{\,new} = \theta_{j}^{\,old} + \eta \sum_{i=1}^{m}[y^{(i)}-\sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}^T\mathbf{x}^{(i)})] x_{j}^{(i)}}\)

Part 7: Going from ascent to descent

All along we worked with gradient ascent. It’s quite simple to write out the update rule for gradient descent. We simply add a minus sign to go in the opposite direction (down rather than up):

\(\boxed {\large {\theta_{j}^{\,new} = \theta_{j}^{\,old} - \eta \sum_{i=1}^{m}[y^{(i)}-\sigma(\boldsymbol{\theta}^T\mathbf{x}^{(i)})] x_{j}^{(i)}}}\)

A note on notation

The above result accords with Sebastian Raschka’s derivation as well, the only difference being I use \(m\) to denote the number of instances rather than \(n\). This reflects standard matrix notation, which is usually denoted as \(m \times n\) with \(m\) denoting the number of rows (instances) and \(n\) representing the number of features/predictors, just like \(Aur\acute{e}lien\,G\acute{e}ron\) uses in Chapter 4 of his book. I used \(p\) instead of \(n\), which is a hat-tip to the statistics community. The symbol \(\pi\) is a bit of unfortunate notation, as it isn’t used in this blog to represent the constant \(3.14...\), but rather a proportion. This is also standard in the stats community.

Wrapping up

I hope this gives you a more clear understanding of the derivation of the logistic regression update rule. The way I’ve presented has several advantages. First, I flesh out all the mathematical details in a step-by-step fashion, making it less likely to get lost. Since this is a foundational topic, it deserves that kind of attention. Secondly, by relying solely on a Chain Rule approach rather than the “hard way” (p.4 of Stanford notes above), you’re better set to expand your skillset into deep learning where there are many more gradients. I’ve showed how each component of the loss function is dealt with by delineating the contribution of each separately, then putting them together with the Chain Rule.

I plan to write up detailed derivations for other machine learning algorithms in the future.