Background

We’ve all probably at some point intended to take a picture of someone or something, only to have our shot photobombed by another object of person. Or maybe we’re recording a video and that happens. Fortunately we have Photoshop and an array of other tools at our disposal, but let’s use Python to see how image stacking can remove unwanted objects from a set of images to produce a single image with the desired object. Another challenge project from Lee Vaughan’s book Impractical Python Projects, this time from Chapter 15.

The train’s a’comin’

I have 8 images that contain a toy train that you can pretend is chugging along on a desk based on its position in various frames. Here’s what the images look like.

Figure 1: Various images of a toy train passing through

The goal is to produce a single image that consists only of the background – that is, the desk. This should be the final outcome:

Figure 2: The outcome after stacking the 8 images above to remove the toy train

Of course, this is a bit silly of an example, but the image stacking in this project can be used for more real-world purposes, like removing unwanted tourists from your vacation pics. The principle will be the same, and that is discussed next.

Methodology

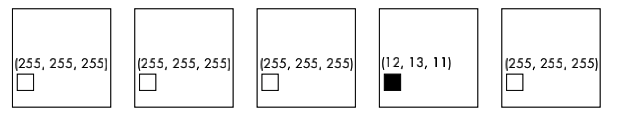

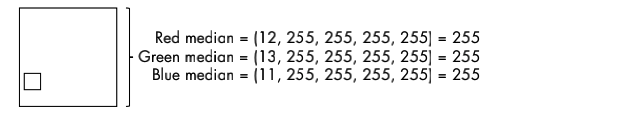

How would you remove an unwanted something from your images by stacking. One of the assumptions is that the background is constant, the only thing moving being the pesky object (maybe a fly). By capturing the RGB (red, green, blue) contents for each pixel and image, we can then take the median across images so that the unwanted object’s RGB gets pushed out.

Figure 3: Stacking images then taking the median across images to remove the black pixel. Source: Impractical Python Projects, p. 344

In Figure 3 we have five images, and we’re looking at the RGB for a particular pixel location. By taking the median of the red, green, and blue pixel densities, we arrive at the final image at the bottom with the blackened pixel removed.

Part 1: Resizing Images

The original images in Figure 1 can be downloaded from train_pics.zip from my Github, where you can also find the full image stacking code I wrote for this project.

Since each image is 4640 x 3480 pixels, the image stacking process would be lengthy without first resizing the images. They’ll be scaled down to a \(1/10\) their original size: 464 x 348. The file name for each rescaled image will include “resized”. Here we’re assuming the original images are stored in a directory (folder) named train_pics.

import os

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

# store the original toy train images files in folder train_pics

os.chdir("train_pics")

for image in os.listdir()[1:]:

with Image.open(image) as img:

img_resize = img.resize((464, 348), Image.ANTIALIAS)

img_resize.save(image.split(".")[0] + "_resized.jpg", quality=95)Part 2: Get the RGB for each pixel in each image

# store the red, blue, and green pixels for each image here

color_keys = ["red", "green", "blue"]

color_dict = {color: [] for color in color_keys}

for image in os.listdir():

if "resized" in image:

with Image.open(image) as img:

for color_idx, color in enumerate(color_keys):

# 0=red, 1=green, 2=blue

color_dict[color].append(list(img.getdata(color_idx)))

os.remove(image)We initialize a dictionary color_dict that stores the RGB values for each of the resized images. The dictionary keys consist of the colors red, green, and blue. The values for each key will be a list of lists. The size of the list is 8 x 161472, the latter number being the product of \(464*348\). That is, the list for key red will contain 8 lists (one list for each of the 8 images), with each of those 8 lists containing 161472 elements, representing the pixel density for red across the entire “area” of the image. This same idea applies for the other colors in the dictionary.

In pillow, we use the getdata method to extract pixel densities, with 0 representing red, 1 representing green, and 2 representing blue.

After we can discard the resized images since we have all the pixel info necessary to create the stacked image.

Part 3: Getting the median pixel densities for the stacked image

medians = {color: None for color in color_keys}

for color in medians:

medians[color] = [

int(np.median(col_gradient)) for col_gradient in zip(*color_dict[color])

]

merged_data = list(

zip(*list(medians.values()))

) # list(medians.values()) has shape (8,161472)We implement the method in Figure 3 with the following code. The medians dictionary will store the median pixel densities for each color. The keys will be the colors red, green, and blue. The values for each key will be a list of size

161472. For each color *color_dict[color] will unpack the list of lists for that color in color_dict. medians will look something like this:

# each list has 161,472 elements

{'red' : [34, 172, 48, 90, 173,...,143, 212, 105, 164],

'green' : [106, 237, 156, 92, 249,...,229, 86, 238, 99],

'blue' : [42, 213, 177, 73, 212, 212,...,111, 131, 134]}We think of the final stacked image as a grid of size 464 x 348, containing 161,472 squares. Each square will have a certain red, green, and blue density. Reading the lists from top to bottom, the first square in the stacked image will have an RGB of (34, 106, 42). The second square will have an RGB of (172, 237, 213), and so on and so forth.

To produce those tuples, we do *list(medians.values()) do produce a list of lists of shape (3, 161472), and then zip it to capture corresponding elements, saving the resultant list of tuples in merged_data.

Part 4: Creating the new image

Finally, we build the new stacked image that has the toy train removed. We call the new method to create a new image of size 464 x 368, and enter the RGB pixel data from merged_data using the putdata method. The show method will display the new image output directly (see Figure 2 above), and you can save it as a .tif using the save method.

stacked = Image.new("RGB", (464, 348))

stacked.putdata(merged_data)

stacked.show()

stacked.save("train_gone.tif", "TIFF")Wrapping up

In real life, obviously I’d use to some image editing software to remove unwanted objects, but this was a good exercise to help me (and you I hope!) better understand how image stacking works under the hood.